Crypto-Economics of the Nervos Common Knowledge Base

| Number | Category | Status | Author | Organization | Created |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0015 | Informational | Draft | Kevin Wang, Jan Xie, Jiasun Li, David Zou | Nervos Foundation | 2019-03-08 |

Crypto-Economics of the Nervos Common Knowledge Base

1. The Objectives of a Token Economics Design

Public permission-less blockchains are open and distributed systems with diverse groups of participants. A well-designed crypto-economics model is to provide incentives so that participants' pursuit of own economic interests leads to desired emergent behaviors in alignment with the protocol, to contribute to the blockchain network's success.

More specifically, the design of a crypto-economic system must provide answers to the following questions:

- How can the economic model ensure the security of the protocol?

- How can the economic model ensure long term sustainability of the protocol?

- How can the economic model align the objectives of different actors to grow the value of the protocol network?

2. The Crypto-economics Design of Bitcoin

The Bitcoin protocol uses its native currency to incentivize miners to validate and produce blocks. The Nakamoto Consensus considers the longest chain as the valid chain, which encourages block producing miners to propagate new blocks as soon as they produce them and validate blocks as soon as they receive them. This ensures that the whole network achieves consensus on the global state.

The native tokens of the Bitcoin network function both as a utility token and an asset. When bitcoins function as a utility, they represent a "Medium of Exchange" (MoE) and can be used to pay transaction fees; when they function as an asset, they represent a "Store of Value" (SoV) and can be used to preserve value over time. The two use cases are not mutually exclusive. They are both important for the network to function. However, it's important to study the economic motives of the users of both use cases as a guide to analyze the sustainability of the Bitcoin network.

The Bitcoin protocol constrains the network's transaction throughput by using a fixed block size limit. Users bid with fees on the limited throughput to have their transactions processed. With this auction like mechanism, transaction fees are determined by the transaction demand - the more demand there is on the network, the higher the transaction fee a user has to pay to beat the competition and have their transaction included in the block.

Bitcoin as a Medium of Exchange Network

The Medium of Exchange use case views the Bitcoin network primarily as a peer to peer value transfer network. MoE users don't have to hold bitcoins to benefit from the network - it's the transactions in themselves that provide value. In fact, there are specialized Bitcoin payment services to provide access to liquidity and allow senders and receivers to acquire and dispose of Bitcoins just in time to perform the value transfer, without having to hold the cryptocurrency. MoE users are not concerned with price or the movement of price but care about the fiat equivalent cost of the transaction fees.

It's challenging for Bitcoin to become a dominant MoE network. If the protocol calibrates its block time and the block size limit, thereby fixing the supply of transactions, the success of the network will necessarily increase the cost of transactions and reduce its competitiveness among other similar purposed blockchains as well as its own forks; If the protocol aims to keep the transaction cost low and increase the supply of transactions with faster block time or bigger blocks, it could compromise both security and decentralization through higher fork rate and increased cost of consensus participation.

Bitcoin as a Store of Value Network

Store of Value users view the Bitcoin network as a protocol to provide security to its native cryptocurrency as an asset that can preserve value over time. They see the Medium of Exchange use case as the necessary function to go in and out of this asset. A store of value user, especially the ones who hold the cryptocurrency for a long time, doesn't care much about the transaction cost, as they can amortize it over time. They do care about the value of a Bitcoin, which depends on the network's security and decentralization - if the network becomes less secure and can be attacked easily, it'll stop being perceived as a store of value and the tokens will lose value; if the network becomes centralized, Bitcoin as an asset no longer has independent value, but has to assume counter-party risk.

For Bitcoin to succeed as an SoV network, it must continue to keep its monetary policy stable and its network secure and decentralized. However, Bitcoin's monetary policy has a hard cap, and after all the coins are mined, the network can only pay for the miners with transaction fees. It's still an open question whether this model could be sustainable, especially considering Store of Value networks themselves tend not to produce many transactions.

Who Compensates the Miners Over the Long Run?

Security and decentralization are two essential properties of a blockchain network, and they come with a high cost that must be paid to the operators of the network. Bitcoin's current model has network security entirely paid with transaction fees after all the coins are mined. However, the MoE users have very limited time exposure to the network's security risk, therefore won't be willing to pay for it; the SoV users have prolonged exposure to the network's security risk and are willing to pay for it, but they produce nearly no transactions.

Bitcoin's consensus mechanism incentivizes miners to recognize the longest chain as the network's canonical state. Miner's ongoing supply of hashing power doesn't only provide security for the current block, but the immutability of all the blocks before it on the canonical chain. Relying on the SoV users to make one time payments for the ongoing security protection they receive from miners is not sustainable.

In an SoV network, relying on inflation to fund network security is more incentive compatible with the users. An inflation based block reward mechanism represents indirect payments from the beneficiaries of the network's ongoing security to the providers of such security, in proportion to the duration that they enjoy the service.

3. Preservational and Transactional Smart Contract Platforms

Smart contract platforms like Ethereum come with Turing-complete programmability and can support a much wider variety of use cases. The native tokens are typically used to price and pay for the cost of decentralized computation. Like the Bitcoin network, smart contract platforms also have the dual functions of preserving value and performing transactions. They differ from the payment networks in that the value they preserve is not only their own native tokens but also the internal states of decentralized applications, for example, crypto-assets ownership in ERC20 smart contracts.

Another significant difference is that transactions on smart contract platforms are much more "portable". It's much easier to take advantage of the more advanced scripting capability of smart contract platforms to develop interoperability protocols to move transactions to a more cost-effective transactional blockchain and then securely settle back to the main "system of record" blockchains.

The economic models of smart contract platforms face similar polarization tendency of payment networks. With their superior interoperable capabilities, smart contract platforms are going to be even more specialized into transactional platforms and preservation platforms. Economically, this bifurcation comes from the fact that the two use cases have different ways of utilizing system resources - transactions consume instantaneous but renewable computation and bandwidth resources, and preservation requires long term occupation of the global state. An economic model optimized for one is unlikely to be optimal for the other.

Competitive transactional platforms need to prioritize for low transaction cost. Transactional users are willing to accept less-optimal security, because of their only moment-in-time, limited exposure to security risk. They're willing to accept the possibility of censored transactions, as long as there are options to take their transactions elsewhere. A transactional platform that invests in either security or censorship resistance will have higher cost of transactions, reflected either with higher transaction fees or high capital cost for stakes in a "stake for access" model, making the network less competitive. This is especially true when a well-designed inter-blockchain protocol can allow trust-less state transfers and fraud repudiation of transactions. We already see examples of transactional users prioritizing cost over security in centralized crypto-asset exchanges and not-so-decentralized blockchains - despite their flaws, they're still popular because of their transactional efficiency.

Competitive preservation platforms need to be sustainably secure and censorship-resistant. It requires an economic model designed not around transactions that happen moment-in-time, but around the ongoing occupation of the global state, and have users pay for the network infrastructure metered in their consumption of this critical resource.

4. Store of Assets

One of the most important use cases for smart contract platforms is to issue tokens to represent ownership of assets. These crypto-assets can have their own communities and markets, and their values are independent of the value of their platform tokens. On the other hand, these assets depend on the platform to process transactions and provide security. Payment networks like Bitcoin can be seen as single asset platforms, where smart contract platforms are multi-asset platforms. Similar to the concept of "Store of Value" in the context of Bitcoin, we call the utility that smart contract platforms preserve the value of its crypto-assets "Store of Assets".

Preservation focused smart contract platforms must have a Store of Assets token economics design. The level of platform security has to grow along with the asset value it preserves. Otherwise, as asset value grows, it will be increasingly profitable to "double-spend" assets by attacking the consensus process of the platform.

None of the current smart contract platforms are designed as Store of Assets platforms. Their token economics are designed either to facilitate transactions (for example, Ethereum's native tokens are to pay for the decentralized computation) or to fulfill staking requirements. In either case, the growth in asset value doesn't necessarily raise miner's income to provide more security.

Every multi-asset platform is an ecosystem of independent projects. The security of the platform can be seen as "public goods" that benefit all projects. To make the ecosystem sustainable from a security point of view, there has to be a clear mechanism that the platform captures the economic success of the ecosystem to raise its own level of security. In other words, a Store of Assets platform has to be able to translate the demand of crypto-assets to the revenue of its miners, often through raising the value of the native tokens with which the miners are compensated. Otherwise, the platform's level of security becomes the ceiling of assets' value. When the value of an asset rises such that typical transactions can no longer be sufficiently protected by the platform, the liquidity would dry up and the demand of the asset would fade.

Decentralized multi-assets smart contract platforms have to be Store of Assets to be sustainable.

5. Decentralization and the Need for Bounded State

Like other long term store of value systems, a Store of Assets platform has to be neutral and free of risks of censorship and confiscation. These are the properties that made gold the world's favorite the store of value for thousands of years. For open, permission-less blockchain networks, censorship resistance comes down to having the broadest consensus scope with a low barrier for consensus and full node participation. Compared to payment networks, running a full node for a smart contract system is more resource intensive. Therefore a Store of Assets platform must take measures to protect the operating cost of full nodes to keep the network sufficiently decentralized.

Both Bitcoin and Ethereum throttle transaction throughput to ensure participation is not limited to only "super computers" - Bitcoin throttles on bandwidth and Ethereum throttles on computation. However, they haven't taken effective measures to contain the ever growing global state necessary for consensus participation and independent transaction validation. This is especially a centralization force for high throughput smart contract platforms, where the global state grows even faster.

In Bitcoin, the global state is the UTXO set, and its growth rate is effectively capped with the block size limit. Users are encouraged to create UTXOs efficiently, since every new UTXO adds overhead to the transaction where it's created, making the transaction more expensive. However, once a UTXO is created, it doesn't cost anything to have it occupy the global state forever.

In Ethereum, the global state is represented with the EVM's state trie, the data structure that contains the balances and internal states of all accounts. When new accounts or new contract values are created, the size of the global state expands. Ethereum charges fixed amounts of Gas for inserting new values into its state storage and offers fixed amounts of Gas as transaction refund when values are removed. Ethereum's approach is a step in the right direction, but still has several issues:

- Neither the size nor the growth rate of the global state is bounded, this gives very little certainty in the cost of full node participation.

- The system raises one-time revenue for expanding the state storage, but miners and full nodes have to bear the cost of storage over time.

- There's no obvious reason why the cost of expanding storage should be priced in fixed Gas amounts, which is designed as measurement to price units of computation.

- The "pay once, occupy forever" state storage model gives very little incentive for users to voluntarily clear state, and do so sooner than later.

The Ethereum community is actively working on this problem, and the leading solution is to charge smart contract "state rent" - contracts have to periodically pay fees based on the size of its state. If the rent is not paid, the contract goes to "hibernation" and is not accessible before the payment is current again. We see several difficult-to-solve problems with this approach:

- Many contracts, especially popular ERC20 contracts, represent decentralized communities and express asset ownership of many users. It's a difficult problem to coordinate all the users to pay for state rent in a fair and efficient way.

- Even if a contract is current on its rent payment, it still may not be fully functional because some of its dependent contracts may be behind on their payments.

- The user experience for contracts with state rent is sub-optimal

We believe a well-designed mechanism to regulate the state storage has to be able to achieve the following goals:

- The growth of the global state has to be bounded to give predictability for full node participation. Ideally, the cost is well within the range of non-professional participants to keep the network maximally decentralized. Keeping this barrier low allows participants of the decentralized network to verify history and state independently, without having to trust a third party or service. This is fundamentally the reason why public blockchains are valuable.

- With bounded growth of the global state, the price for expanding it and the rewards for reducing it should be determined by the market. In particular, it's desirable to have the cost of expanding state storage higher when it's mostly full, and lower when it's mostly empty.

- The system has to be able to continuously raise revenue from its state users to pay miners for providing this resource. This serves both purposes of balancing miner's economics and providing incentives for users to clear unnecessary states sooner than later.

Just like how Bitcoin throttles and forces pricing on bandwidth and Ethereum throttles and forces pricing on computation, to keep a blockchain network long term decentralized and sustainable, we have to come up with a way to constrain and price the global state. This is especially important for preservation focused, Store of Assets networks, where usage of the network is not about transactions that mostly happen off-chain, but ongoing occupation of the global state.

6. The Economic Model of the Nervos Common Knowledge Base

The Nervos Common Knowledge Base (Nervos CKB for short) is a preservation focused, "Store of Assets" blockchain. Architecturally, it's designed to best support on-chain state and off-chain computation; economically, it's designed to provide sustainable security and decentralization. Nervos CKB is the base layer of the overall Nervos Network.

Native Tokens

The native token for the Nervos CKB is the "Common Knowledge Byte", or "CK Byte" for short. The CK Bytes represent cell capacity in bytes, and they give owners the ability to occupy a piece of the blockchain's overall global state. For example, if Alice owns 1000 CK Bytes, she can create a cell with 1000 bytes in capacity, or multiple cells that add up to 1000 bytes in capacity. She can use the 1000 bytes to store assets, application state, or other types of common knowledge.

A cell's occupied capacity could be equal to or less than its specified capacity. For example, for a 1000 byte cell, 4 bytes would be used to specify its own capacity, 64 bytes for the lock script and 128 bytes for storing state. Then the cell's current occupied capacity is 196 bytes, but with room to grow up to 1000 bytes.

The smallest unit of the native token is "CK Shannon": 1 CK Byte = 100_000_000 CK Shannons.

"CK Shannon" is the indivisible unit.

"CK Shannon" is designed for the scenes that people want to transfer value less than one "CK Byte".

Token Issuance

There are two types of native token issuance. The "base issuance" has a finite total supply with a Bitcoin like issuance schedule - the number of base issuance halves approximately every 4 years until all the base issuance tokens are mined out. All base issuance tokens are rewarded to the miners as incentives to protect the network.

The "secondary issuance" is designed to collect state rent, and has issuance amount that is constant over time. After base issuance stops, there will only be secondary issuance.

Collecting State Rent with Secondary Issuance and the NervosDAO

Since the native tokens represent right to expand the global state, the issuance policy of the native tokens bounds the state growth. As state storage is bounded and becomes a scarce resource like bandwidth in Bitcoin and computation throughput in Ethereum, they can be market priced and traded. State rent adds the necessary time dimension to the fee structure of state storage occupation. Instead of mandating periodic rent payments, we use a two-step approach as a "targeted inflation" scheme to collect this rent:

- On top of the base issuance, we add the secondary issuance which can be seen as "inflation tax" to all existing token holders. For users who use their CK Bytes to store state, this recurring inflation tax is how they pay state rent to the miners.

- However, we would have also collected rent from the CK Bytes that are not used to store state, and we need to return to them what we collected. We allow those users to deposit and lock their native tokens into a special contract called the NervosDAO. The NervosDAO receives part of the "secondary issuance" to make up for the otherwise unfair dilution.

Let's suppose at the time of a secondary issuance event, 60% of all CK Bytes are used to store state, 35% of all CK Bytes are deposited and locked in the NervosDAO, and 5% of all CK Bytes are kept liquid. Then 60% of the secondary issuance goes to the miners, 35% of the issuance goes to the NervosDAO to be distributed to the locked tokens proportionally. The use of the rest of the secondary issuance - in this example, 5% of the that issuance - is determined by the community through the governance mechanism. Before the community can reach agreement, this part of the secondary issuance is going to be burned.

For long term token holders, as long as they lock their tokens in the NervosDAO, the inflationary effect of secondary issuance is only nominal. For them it's as if the secondary issuance doesn't exist, and they're holding hard-capped tokens like Bitcoin.

Miner Compensation

Miners are compensated with both block rewards and transaction fees. They receive all the base issuance, and part of the secondary issuance. In the long term when base issuance stops, miners still receive state rent income that's independent of transactions but tied to the adoption of the common knowledge base.

Paying for Transaction Fees

A decentralized blockchain network's transaction capacity is always limited. Transaction fees serve the dual purposes of establishing a market for the limited transaction capacity and as protection against spams. In Bitcoin, transaction fees are expressed with the difference between the outputs and inputs; In Ethereum, the user specify the per computation unit price they're willing to pay with gasprice, and use gaslimit to establish a budget for the entire transaction.

To ensure decentralization, the Nervos CKB restricts both computation and bandwidth throughput, effectively making it an auction for users to use those system resources. When submitting a transaction, the user can leave the total input cell capacities exceeding the total output cell capacities, leaving the difference as transaction fees expressed in the native tokens, payable to the miner that creates the block containing the transaction.

The number of units of computation (called "cycles") are added to the peer-to-peer messages between the full nodes. When producing blocks, miners order transactions based on both transaction fees and the number of computation cycles necessary for transaction validation, maximizing its per-computation-cycle income within the computation and bandwidth throughput restrictions.

In the Nervos CKB, the transaction fees can be paid with the native tokens, user defined tokens or a combination of both.

Paying for Transaction Fees with User Defined Tokens

Users are also free to use other tokens (for example, stable coins) to pay transactions fees, a concept known as "Economic Abstraction". Note that even without explicit protocol support, it's always possible to have users make arrangements with miners to pay transaction fees in other tokens outside of the protocol. This is often seen as a threat for many platforms - if the platform's native tokens are purely to facilitate transactions, this would take away its intrinsic value and cause a collapse.

With the Nervos CKB, economic abstraction is possible because the payment methods are not hard-coded in transactions. We embrace economic abstraction and the benefits it brings. Since the intrinsic value of the native tokens is based not on transaction payment, economic abstraction doesn't pose a threat to the stability of our economic model. We do expect, however, the native tokens themselves are going to be the payment method of choice for vast majority of users and use cases - the native tokens are going to be the most widely held tokens in the Nervos ecosystem, and everyone who owns assets necessarily owns the Nervos natives tokens as state storage capacity that the assets occupy.

For more a more detailed analysis on transaction payments, please see Appendix 1.

7. An Economic Model Designed for Preservation

The economic model of the Nervos CKB is designed specifically to preserve assets and other types of common knowledge. Let's bring back the 3 high level design goals and examine our design in this context:

- How can the economic model ensure the security of the protocol?

- How can the economic model ensure long term sustainability of the protocol?

- How can the economic model align the objectives of different actors to grow the value of the protocol network?

Security and Sustainability of the Protocol

The main design choices we made to ensure security of the Nervos CKB as a "Store of Assets" protocol are:

- Our native tokens represent claim to capacity in the state storage. This means the demand to holding assets on the platform directly puts demand on owning the native tokens. This creates an effective value capture mechanism into the native tokens from the assets they preserve. We claim that this is the only sustainable way that a "Store of Assets" platform can grow its security budget over time, instead of entirely basing it on speculation and altruism.

- The secondary issuance makes sure miner compensation is predictable and based on preservation demand instead of transactional demand. It also eliminates potential incentive incompatibility of the Nakamoto Consensus nodes after block reward stops. This is also important in a future when most transactions move to the layer 2, leaving a starved layer 1.

- The NervosDAO serves as the counter-force to the inflationary effects of secondary issuance, to ensure long term token holders are not diluted by this issuance.

For a purpose of keeping the network decentralized and censorship resistant, we believe it's important to limit the resource requirements of consensus and full nodes. We protect the operating cost of nodes by regulating the throughput of computation and bandwidth, similar to how it's accomplished with Bitcoin and Ethereum. We regulate the state storage with a combination of a "cap and trade" pricing scheme and opportunity cost based cost model for storage users.

Aligning the Interests of Network Participants

In a typical smart contract platform, participants of the network have different interests - users want cheaper transactions, developers want adoption of their applications, miners want higher income, and holders want appreciation of their tokens. Those interests are not well aligned, and oftentimes in conflict - for example, more adoption won't give cheaper transactions (they'll be more expensive as more demand is put on the blockchain); cheaper transactions won't give more income to the miners; higher token price won't help with transaction cost (the opposite could happen if users don't adjust their local transaction fee setting). Decentralized computation platforms provide value through processing transactions. The price of their tokens doesn't materially change the intrinsic value of the network. For example, Ether's price doubling doesn't increase or decrease Ethereum's intrinsic value as a decentralized computation platform, because the introduction of Gas in the first place is to de-couple the price of computations from the price actions of Ether the cryptocurrency. This makes token holders of Ethereum only take the role of a speculator, instead of active contributors that can increase the value of the network.

In the Nervos CKB, Store of Assets users want security of their assets; developers want more adoption, reflected in more assets preserved; miners want higher income and token holders want price appreciation of their tokens. Higher token price supports everyone's objective - the network would be more secure, miners get higher income, and token holders get better return.

Aligning all participants' incentives allows the network to best harness network effects to grow its intrinsic value. It also produces a more cohesive community and makes the system less prone to governance challenges.

Bootstrapping Network Effect and Network Growth

As the network grows to secure more assets and common knowledge, more native tokens of the Nervos CKB are going to become occupied. This accrues value to the native tokens by reducing circulating supply and providing positive support to the market price of the tokens. The higher price and increased share of secondary issuance motivate miners to expand operations and make the network more secure, increasing the intrinsic value of the network and the native tokens, attracting more and higher value preservation usage.

The pro-cyclical loop of the network's adoption and network's intrinsic value provides a powerful growth engine for the network. Combined with how the network's value accrues to the native tokens and gets captured by long term holders, it makes the network's native token an excellent candidate for store of value. Compared to Bitcoin as a monetary store of value, the Nervos CKB is similarly designed to be secure and long term decentralized. We believe Nervos CKB has a more balanced and sustainable economic model than Bitcoin, and also comes with the intrinsic utility of securing crypto-assets and common knowledge.

Developer's Cost in a "First Class Asset" Platform

In Ethereum, the top-level abstraction is its accounts. Assets are expressed as state owned by smart contract accounts. In the Nervos CKB, assets are the first class abstraction with cells, where ownership is expressed with the lock script of a transaction output, a concept known as "First Class Assets". In other words, just like Bitcoin, assets in the Common Knowledge Base are owned by users directly instead of being kept custody in a smart contract.

The "First Class Asset" design allows the state storage cost of owning assets put not on developers, but on individual users. For example, a developer could create a User Defined Token with 400 bytes of code as validation rules, and every record of asset ownership would take 64 bytes. Even if the assets were to have 10,000 owners, the developer would still only need to use 400 CK Bytes.

For developers, we expect the capital cost of building projects on the CKB is moderate even in a scenario that the price of the native tokens were to go up degrees of magnitude higher. For users, the cost of the 64 CK Bytes to own an asset on the Nervos CKB would also be trivial for a long time even in the most aggressive adoption assumption of the platform.

In the future where those cost were to become meaningfully expensive, it's always possible for developers to rely on lending to bootstrap their projects and for users to move their assets off the Common Knowledge Base on to other transaction blockchains in the Nervos Network if they're willing to take the corresponding trade-offs. Please see the "Nervos Network" section for more details.

Lending

Nervos CKB will support native token lending to improve the liquidity of the CK Bytes thanks to the programming ability provided by CKB-VM and the Cell model. Since the utility of the native token is realized through possession instead of transactions, it's possible to have risk-free un-collateralized lending for CK Bytes locked for known duration of time. Entrepreneurs can borrow the CK Bytes they need with much lower capital cost for a period such as 6 months to work on prototypes and prove their business model. Long term users can lend out their tokens to earn extra income.

The effective interest rate of lending is determined by the market supply and demand, but the current state of token utilization also plays a big role. Higher utilization of the available global state means fewer tokens can be made available for lending. This makes the lending interest higher and makes it more attractive to release state and lock tokens in the NervosDAO to earn income. It serves the purpose to help reduce the global state: lower utilization of the available state means more tokens can be lent out. It makes the lending interest rate lower to encourage adoption.

Nervos Network

The Nervos CKB is the base layer of the Nervos Network with the highest security, decentralization, transaction cost and state storage cost. Just like how Bitcoin and Ethereum could scale off-chain with lightning network and plasma solutions, Nervos CKB also embraces off-chain scaling solutions and allow users to preserve and transact assets off-chain. When using off-chain solutions, users and developers can choose their own trade-offs between cost, security, latency and liveness properties.

Owning and transacting assets on the Nervos CKB come with the highest capital and transaction cost, but is also the most secure. It's best suited for high value assets and long term asset preservation; Layer 2 solutions can provide scaling for both transaction throughput and state storage, but they would come with either weakened security assumptions or mandate extra steps of repudiation. They also often require participants to be online within a time window. If both are acceptable (likely for owning and transacting low value assets for short duration), the Nervos CKB can be used as security anchor to other transaction blockchains, to effectively magnify both its transaction and state storage capacities.

If operators of transaction blockchains don't want to introduce extra security assumptions, they can mandate that high value assets be issued on the CKB and low value assets be issued on transactional blockchains. Then they can use CK Bytes on the CKB to store periodic block commits, challenges and proofs from the transactional blockchains - critical common knowledge for secure off-chain transaction repudiation. If a transaction chain doesn't mind introducing an extra layer of security assumption with a committee-based consensus protocol, they could also have their validators bond CK Bytes on the CKB to explicitly adjust security parameters.

8. Applications of the Token Economics Model

The economic model of the Nervos CKB provides building blocks that application developers can use directly as part of their own economic model. We'll list subscriptions and liquidity income as two such possible building blocks.

Subscriptions

Recurring payment or subscription is a typical economic model for services offered on the blockchain that span over some duration of time. One such example is the off-chain transaction monitoring service that's often needed for layer 2 solutions. On the Nervos CKB, duration based services can ask their users to lock certain amount of native tokens in the NervosDAO and designate the service providers as the beneficiaries of the generated interest income in a subscription based model. Users can stop using the services by withdrawing their tokens from the NervosDAO.

In fact, Store of Assets users that occupy global state can be seen as paying an ongoing subscription metered by the size of their state, and the beneficiaries are the miners that provide the security service.

Liquidity Income

In a Plasma like layer 2 solution, a typical pattern is that users would deposit native tokens in a smart contract on the layer 1 blockchain in exchange for transaction tokens on the layer 2. A layer 2 operator with sufficient reputation can have users commit to fixed duration deposits, and then use such deposits to provide liquidity to the lending market and earn income. This gives operators of layer 2 solutions an additional revenue stream on top of the fees collected on layer 2.

Appendix 1: Transaction Cost Analysis

Nervos CKB uses Proof of Work based Nakamoto consensus, similar to what's used in Bitcoin - for more details, please see the "Nervos Consensus Paper"

The economics of the consensus process is designed to incentivize nodes to participate in the consensus process and provide measurements that nodes can use to prioritize transactions. At the core, it's designed to help consensus nodes answer the question: "Is this transaction worth to be included in the next block if I had the opportunity to produce the block?"

A block producing node can do a cost/benefit analysis to answer this question. The benefit of including a transaction is to be able to collect its transaction fee, and the cost of including a transaction in a block has three parts:

- Fee Estimation Cost (

): this is the cost to estimate the maximum possible income if a node where to include a transaction

): this is the cost to estimate the maximum possible income if a node where to include a transaction - Transaction Verification Cost (

): blocks containing invalid transactions will be rejected by the consensus process, therefore block producing nodes have to verify transactions before including them in a new block.

): blocks containing invalid transactions will be rejected by the consensus process, therefore block producing nodes have to verify transactions before including them in a new block. - State Transition Cost (

): after a block is produced, the block producing node has to perform local state transitions defined by state machines of the transactions in the block.

): after a block is produced, the block producing node has to perform local state transitions defined by state machines of the transactions in the block.

In particular, transaction verification,  has two possible steps:

has two possible steps:

: Authorization Verification Cost

: Authorization Verification Cost : State Transition Verification Cost

: State Transition Verification Cost

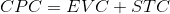

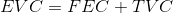

We use CPC and EVC to represent Complete Processing Cost and Estimation and Verification Cost:

- CPC: Complete Processing Cost

- EVC: Estimation and Verification Cost;

Bitcoin's Transaction Cost Analysis

Bitcoin allows flexible authorization verification with the Bitcoin Script. Users can script the authorization rules and build smart contracts through  when creating transactions. Bitcoin has a fixed state transition semantic, which is to spend and create new UTXOs. In Bitcoin, the result of the state transitions are already included in transactions, therefore the State Transition Cost (STC) is 0.

when creating transactions. Bitcoin has a fixed state transition semantic, which is to spend and create new UTXOs. In Bitcoin, the result of the state transitions are already included in transactions, therefore the State Transition Cost (STC) is 0.

Bitcoin uses the amount difference of the inputs and outputs to express transaction fees. Therefore, the cost of estimating transaction fees scales to  where

where  is the total number of inputs and outputs.

is the total number of inputs and outputs.

Authorization verification in Bitcoin requires running scripts of all inputs. Because the Bitcoin Script prohibits JUMP/looping, the computation complexity can roughly scale to the length of the input scripts, as , where

, where  is the number of inputs and

is the number of inputs and  is the average script length of an input. Therefore, the total cost of

is the average script length of an input. Therefore, the total cost of  roughly scales to the size of total transaction.

roughly scales to the size of total transaction.

Bitcoin's state transition rules are simple, and nodes only have to verify the total input amount is the same as the total output amount. Therefore, the  in Bitcoin is the same as

in Bitcoin is the same as  , also scaling to

, also scaling to  .

.

In total, Bitcoin's cost of processing a transaction roughly scales to the size of the transaction:

Ethereum's Transaction Cost Analysis

Ethereum comes with Turing-complete scriptability, and gives users more flexibility to customize state transition rules with smart contracts. Ethereum transactions include gaslimit and gasprice, and the transaction fees are calculated using the product of their multiplication. Therefore,  is

is  .

.

Unlike Bitcoin, Ethereum's transactions only include the computation commands of state transitions, instead of the results of the state transitions. Therefore, Ethereum's transaction verification is limited to authorization verification, and doesn't have state transition verification. The rules of authorization verification in Ethereum are:

- Verify the validility of the Secp256k1 signatures, with computation complexity of

- Verify the nonce match of the transaction and the account that starts the transaction, with computation complexity of

- Verify the account that starts transaction has enough ether to pay for the transaction fees and the amount transferred. This requires access to the account's current balance. Ignoring the global state size's impact on account access, we can assume the complexity of this step is also

.

.

Based on the above, the overall authorization verification complexity in Ethereum is  .

.

Since every byte of the transaction data comes with cost  , the larger

, the larger  is, the more gas it needs, up to the gaslimit

is, the more gas it needs, up to the gaslimit  specified. Therefore,

specified. Therefore,

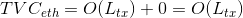

Ethereum comes with a Turing complete VM, and the computation of the result state could include logic of any complexity. Ethereum transaction's  caps the upper bound of computation, therefore

caps the upper bound of computation, therefore  。To summarize all the above:

。To summarize all the above:

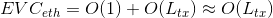

Different from Bitcoin,  for the Ethereum nodes is less than

for the Ethereum nodes is less than  . This is because Ethereum nodes only compute the result state after transactions are included in the block. This is also the reason that transaction results on Ethereum could be invalid, (e.g. exceptions in contract invocation or the gas limit is exceeded), but the Bitcoin blockchain only has successfully executed transactions and valid results.

. This is because Ethereum nodes only compute the result state after transactions are included in the block. This is also the reason that transaction results on Ethereum could be invalid, (e.g. exceptions in contract invocation or the gas limit is exceeded), but the Bitcoin blockchain only has successfully executed transactions and valid results.

Nervos CKB's Transaction Cost Analysis

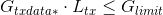

Nervos CKB's transactions are structured with inputs and outputs, similar to Bitcoin's. Therefore, the  and

and  for the Nervos CKB are the same as those of Bitcoin's:

for the Nervos CKB are the same as those of Bitcoin's:

Because CKB transactions include the result of the transactions as outputs, therefore:

Cycles as Measurement Units of Computation Complexity

We introduce "cycle" as a unit of measurement for computation complexity in the CKB, similar to the "gas" concept in Ethereum. Nervos CKB's VM is a RISC-V CPU simulator, therefore cycles here refer to real CPU computation cycles in the VM. The cycle number for an instruction represents the relative computation cost of that instruction. Transactions in the Nervos CKB require the sender to specify the number of cycles required for its verification. Nodes can opt to set an acceptable cycle upper bound cyclemax, and only process transactions with fewer cycles. We'll also introduce cycles to a block, with its value equal to the sum of all specified transaction cycles. The value of cycles in a block can't exceed the value blockcyclesmax, which are set and can be automatically adjusted by the system.

Nodes can set their cyclemax to different values. cyclemax only impacts how a block producing node accepts new transactions, not how a node accepts transactions in a new block. Therefore, it's not going to cause inconsistency in the validation of blocks. A valid block needs valid proof of work, and this cost discourages a block producing node to include an invalid transaction with high cycles value.

The following table shows the runtime differences in Bitcoin, Ethereum and the Nervos CKB.

Authorization ( ) ) | State Validation ( ) ) | State Transition( ) ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin | Generalized | Fixed | None |

| Ethereum | Fixed | None | Generalized |

| CKB | Generalized | Generalized | None |

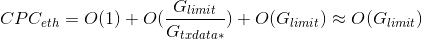

Here's a summary of the computational complexity of different parts of the consensus process for Bitcoin, Ethereum and Nervos CKB ( means cycle limit)

means cycle limit)

|  |  |  |  | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin |  |  |  |  |  |

| Ethereum |  |  |  |  |  |

| CKB |  |  |  |  |  |

CKB Docs

CKB Docs